(Continued from previous post located HERE)…

TO REDEEM THE PAST:

Glimpses of the Great War based on the letters of Eric Standring

©2014 All Rights Reserved

Training

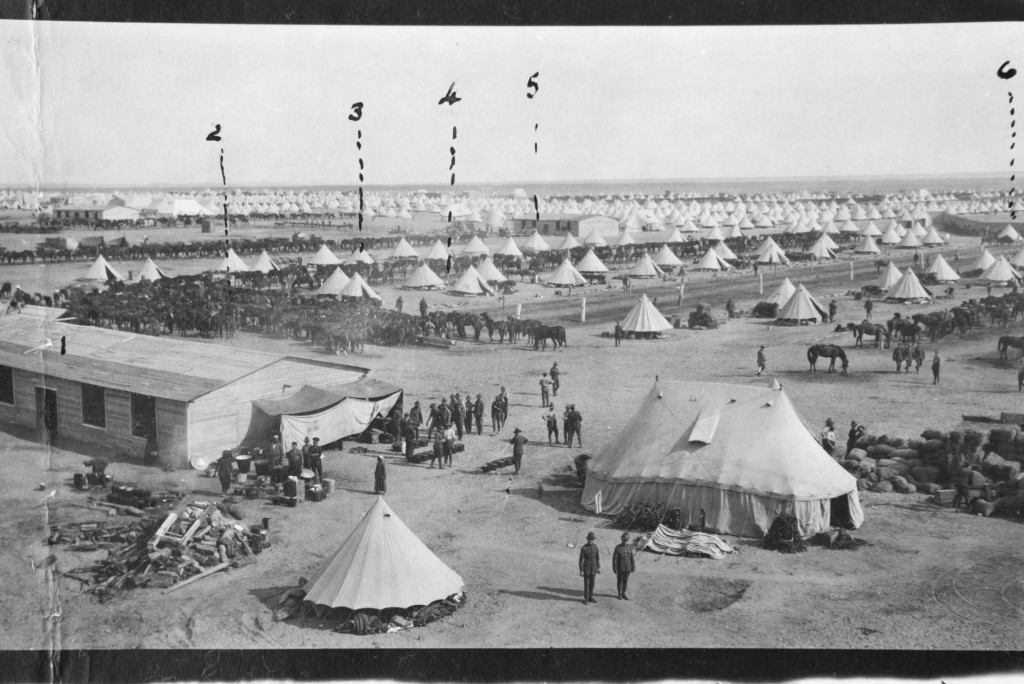

The OMR used their time in camp to prepare for what they expected to come.

We have had a 36 hour engagement the other day, about 40,000 troops taking part in it. You want to see that number to realise what a mob of there must be at the front. All the artillery have live shell practice. We have been getting the horses used to it by having them just behind the guns. Then the guns fire over our heads from about 2 miles distance, then we go up to about 300 yards of where they are bursting. And guns make a great bang and the flame shoots out about a chain. Then there is a most awful whining, tearing sound like a giant going who-o. When you are near the bursting point you can plainly see the shell coming, but you can’t see it near the gun. The instant the shell hits the ground it explodes with a great roar. The shrapnel shells burst in the air and cut up the ground all round.

The horses were a bit mad at first but now they only prick up their ears and snort a bit. It is marvelous how sagacious they are. We can get off and they know what to do at once. We always start by whistles. I was sort of daydreaming the other day when the whistle went to advance at the trot. My horse heard the whistle and was off like a shot, nearly emptying me out of the saddle. They hardly need any guide now in wheeling and will walk quickly and quietly along on the march. They seemed quite a different lot to the savages as we had in Tahuna.

Illnesses

Eric had a number of hospital admissions. Quite early on he was in an isolation hospital for two weeks with scabies. He had to wait in hospital for some new clothes. He was released from hospital and complained that he got boils.

Eric is pleased to get NZ papers but notes that many of the chaps hear of deaths of relatives from the NZ papers rather than official sources. The chaps were amused to see a mention in the papers including a fulsome article in the “Otago Daily Times” that Eric is injured.

The article in the Otago Daily Times read:

TROOPER STANDRING. Advice has been received that Trooper Hubert Eric Standring is amongst the sick and wounded in the Victoria College Hospital, Alexandria. He is the fourth son of the Rev. J. Standring, of Middlemarch, and was born in Invercargill in November,1894. Until he was 17 he resided with his parents at the Waiareka Manse, Enfield, Oamaru.

He was educated at the Teaneraki School, from which he passed by proficiency to the Waitaki Boys’ High School. There he was an officer in the school cadets; and, after passing with credit the civil service examination, was offered a post in the Public Works Department, which he accepted. On the outbreak of hostilities he joined the Main Body of the Expeditionary Force as a member of the 12th (Otago Mounted) Regiment. His genial disposition has gained him many friends, and numerous expressions of sympathy have been received by his parents.

He was in the Victoria College Hospital. In this instance though the army records show he was hospitalized for phimosis defined in the dictionary as “constriction or non-retractability of the foreskin”.

Sidi Bishr

By May, 1915 most of the OMR had been sent to Gallipoli, with a skeleton force of 114, including Eric, being left behind to manage the horses. On 23 May the OMR moved to Sidi Bishr on the eastern side of Alexandria, near the coast.

Eric advises that he has been learning Arabic.

I will have a great lot to tell you when I come back as this is truly an ancient and wonderful country.

He writes to Gladys that she would be enchanted with scene with white sand, sea blue and date palms everywhere. Swimming is good. The Arab and Egyptian kids do not wear much. Flies swarm over them. It is so warm, Eric sleeps on the sand in the open on an oil sheet with just a blanket on top. He complains about the food.

An Indian regiment, the Mule Cart Transport is camped next door and is a great fascination to Eric. He describes the Indians killing sheep with a kukri. He is impressed at how well they look after their mules, and have already served in Belgium. Eric visits the Indian camp some time and is given curry and chapattis.

By July 1915, Eric is mentioning the Dardanelles. Most of the regiment had gone to Gallipoli.

Officers are coming back and saying we are only holding on to the Peninsula by the “skin of our teeth”. Our men at the Dardanelles have had a big lot of casualties.

Every fit man is being sent to Gallipoli.

The Major does not want me to leave and I have been promised sergeant’s stripes if I stay but I reckon it is my duty to go.

He got his sergeants stripes and, according to his service record he left Alexandria for the Dardanelles on 17 August 1915.

Gallipoli

When he initially landed in Gallipoli, Eric was chosen to go with the Major to General Headquarters. The OMR commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Bauchop had been killed and the Major was taking over.

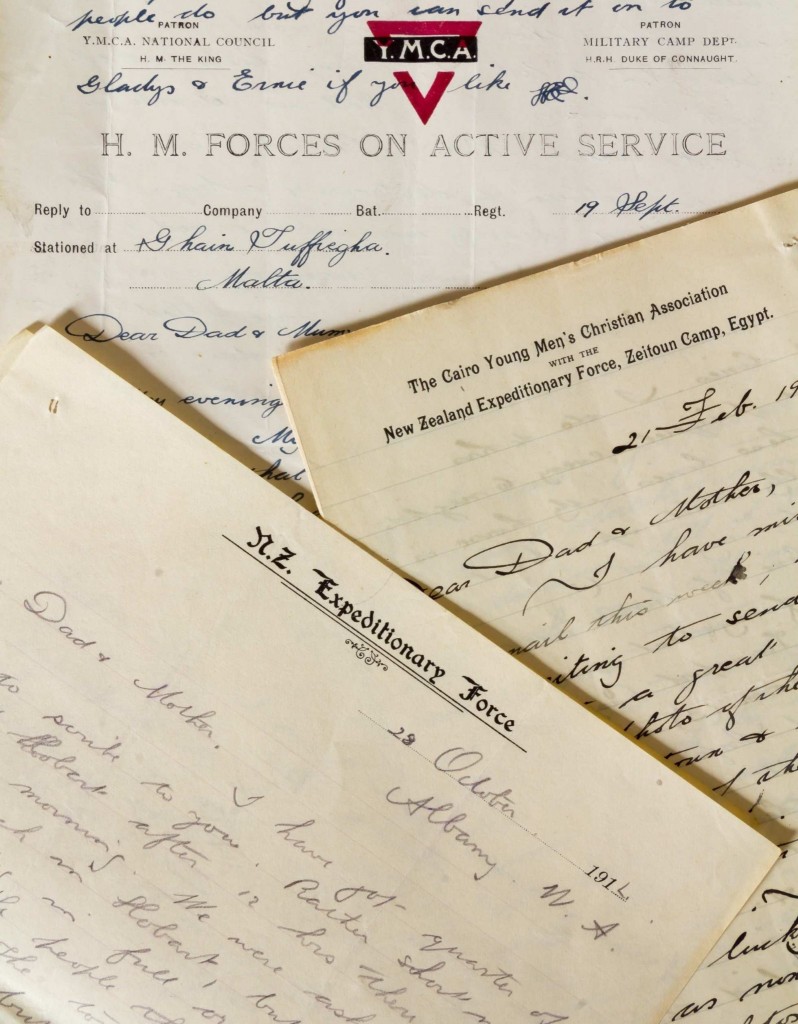

Eric sent one letter from Gallipoli, written in pencil on pages torn out of a notebook.

I have been over here for the last month and have been under fire nearly all the time. I am well and in good spirits but am wishing for the war to close as it is not what it is cracked up to be. The day is very hot and I am squatting in my home which is simply a hole in the ground with a bit of the sheet on the top. I sleep and live in it, although this place is pretty safe.

We get some shrapnel in the early morning and evening, during the day it is quiet. You would not think it quiet but we do, easy to not notice machine guns and rifles firing after the first week.

I was in charge the other day and was one of the very few who came out alive. About 12 of us got into the new trench past the one we should have got into and three of us got out alive. My luck was absolutely in as I got my haversack cut away by a piece of shell, a bullet grazed through my left forearm, a piece of bomb just an inch below my eye and a cut in the jaw from a splinter. None of them were serious enough to be sent away with but they are sore.

I dare not write more about this place as the whole letter will be condemned by censors. There are millions and millions of flies here. There’s no chance of burying the dead so that is why.

The wounds he received became infected and he was taken off Gallipoli on 8 September. Over the next weeks several of his letters contained glimpses of the horrors he had encountered.

On 13 September, by which time he was in Malta, he wrote a more detailed account of the charge. He was involved in the fighting at Hill 60. This was the last major offensive on Gallipoli and capped a horrendous period for the OMR. The description he gives appears to support it being in the second attack on 27 August 1915. When fighting ended after two days the hill was still very much in control of the Turks. The following letter, with slight omissions was published in the “Oamaru Mail” and part of it also appears in the history of the OMR.

There were twelve of us, mostly Wellington Mounted Rifles, and one or two Australians advancing along one of the captured trenches or rather one of the trenches being captured. We got too far, and the rest got killed behind.

We came to a corner and behind that, about ten yards off there were hundreds of Turks blazing away. The sergeant who put his head round first was shot through the head instantly. The Abduls then began blazing in bombs. They were percussion bombs and most of them landed in the traverse and did little damage to us crouched in the trench.

A young chap of the WMR stood in the corner of the traverse and I knelt beside him handing up the bombs as soon as I could light them. Poor chap, he did not last long! He did not take one bomb I had lit immediately so I looked up, and he was standing up straight with all his head blown off bar a bit of the back. I threw the bomb and took his place; threw two or three more, and then shot a Turk right off the muzzle of my rifle. He had sneaked up to the corner and was going to drop a whole swag of bombs over. One or two landed over me and killed several of the chaps, then one burst right beside me, and that was all I knew till a good while after. One of the chaps, afterwards killed, dragged me back to the next corner. I soon realised where I was again. I hardly dared feel my face and jaw in case they were blown off. However, they were just scratches on my eye and jaw, but a fair hole in my arm and knee, and a scratch on my shoulder.

There were only five of us left then. We had to get out as best way we could as the Turks came on to every corner as we left it and we had no more bombs. They were absolutely game to death. Well we got back and came to a place and found Turks barring the way, but fortunately for us, as soon as they saw us they bolted like rabbits down a side trench and we got clear.

Our own shells began to come perilously near as they were firing at the advancing Turks. Two of us got a little bit behind, one of our own shells burst on the parapet and blew one to pieces, and the other’s arms off. He came on but soon sank and, I suppose, died.

We came up then to about twenty of the Tommies and determined to hold about the last fifty yards, built a barricade. It was now nearly dark. The Turks rained in dozens of bombs in. We threw some back, put a coat over some as they lay before bursting, which stops the pieces flying pieces to a great extent. Others blew some of the chaps to little pieces.

I got a scratch on the back of the shoulder from rifle fire. The bullet landed in the middle of my haversack on my shoulder and drove the buckle in. It was nothing alarming. We then decided to make a rush back to a trench captured by our men in the early afternoon. We had to cross about thirty yards under a furious fire, and it was every man for himself. Two of us got up together and made a rush. Half way was a trench half filled with dead Turks—dead a fortnight.

The other chap fell just as we got to it, so I jumped in and sat on the dead for a while. That is how I got my knee poisoned, I think, as they were nearly liquid. I could stand it no longer, so got up and made another rush and got safely to our trench. We had very heavy fire all right but it slackened off about daylight. I found two of the twelve who were with me at the start. We were absolutely yellow from the proximity of our own lyddite shells, and the Turks’ bombs, which are filled with picric acid.

I came down to the dressing station, got my wounds dressed and went back to the trenches but we were all sent down to the bivouacs about an hour after. I had to have a big tot of rum or I wouldn’t have walked there.

In the trench we were driven out of you could not possibly put your foot down for dead Turks, and in places they almost filled the trench, piled one on top of the other. Some were blown into just heaps of flesh, and all were terribly shattered. Our boats shelled these trenches for just one hour before the assault, but in that time they fired 500 shots from 4 and 6-inch guns.

As we lay under the shelter of a little bank and they went whining overhead and bursting about 300 yards off in the case of high explosives, and just overhead with shrapnel the noise was absolutely awful. It made a man realise how small he is. The big shells come, soughing along at a very slow rate, but the noise and ground they kick up is stupendous. They come along like someone saying “Phew-w-w”, then “Bang whiz”! The smaller shells make a great whiz but don’t make much of a bang.

In another letter Eric detailed his arrival on Gallipoli which included the following.

One place we passed a dressing station. It was full of groaning men and in one row was about to nine or 10 stretchers with their burden covered up but still with the blood oozing out in drops and running down the hill. On an operating table was a man, the young doctor was trying to fix him up a little. Both legs appeared to be shattered and one arm and all the lower part of his chin from the lower lip to the point move was shot away. They were doing the best but he was even able to moan for water but could not swallow it. The doctor and his orderly just went on quietly sponging and splinting his legs though there was no hope of him pulling through. That scene made me realise it was war we had come to.

(Continued in Next Post…)

(If you have missed reading parts of this series, please Start Here)

(If you would like to move on to the next post, Click Here)